Primary infections of mummy berry disease of blueberry are initiated by wind-borne spores called ascospores. These spores are released from mushrooms (apothecia) that develop from mummified, overwintered blueberries from the previous season (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Disease cycle of mummy berry of blueberry. Annemiek Schilder, Michigan State University

In 2017 in Whatcom and Skagit counties, apothecia have ceased releasing ascospores and infections of floral and vegetative tissues have started to appear in affected blueberry fields. These primary symptoms are referred to as “blight” and/or flower and shoot strikes and can generally be controlled by timely fungicide applications during ascospore release and bud break. However, during 2017 record rainfall has been seen in these counties during March and April resulting in standing water in blueberry fields and precluding fungicide applications aimed at the primary disease cycle in many fields.

Shoot strikes first appear as browning along the major leaf veins that spreads over the leaf blade and eventually covers the whole leaf cluster (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Mummy berry shoot strike symptoms: early (left/top) and late stage (right/bottom) of symptom appearance.

A light grey powdery layer of spores (conidia) can be found at the base of the leaf. Floral strikes appear as browned, shrunken floral clusters that also present gray fungal growth on the pedicel (Fig. 3). At this stage, where the pathogen is producing conidia on the infected tissues, the pathogen mimics flowers by secreting sugars and odors, and reflecting UV light in a way that it attracts insects. Bees land on the tissues and transport conidia into flowers along with the pollination process (Batra and Batra 1985). The transport of conidia mostly occurs by bees, but also by other insects (McArt et al. 2016) and wind (Cox and Scherm 2001). Once on the floral stigma, conidia germinate and colonize the stigma, style and ovary (Fig. 4) preventing development into healthy fruit, instead returning a mummified shriveled, white berry that can’t be eaten or sold (Fig. 1 and 5).

Figure 3: Mummy berry flower strike symptom.

Figure 4: Infection pathway of mummy berry pathogen in flower.

Figure 5: Mummy berry infected fruit

Management of fruit infection

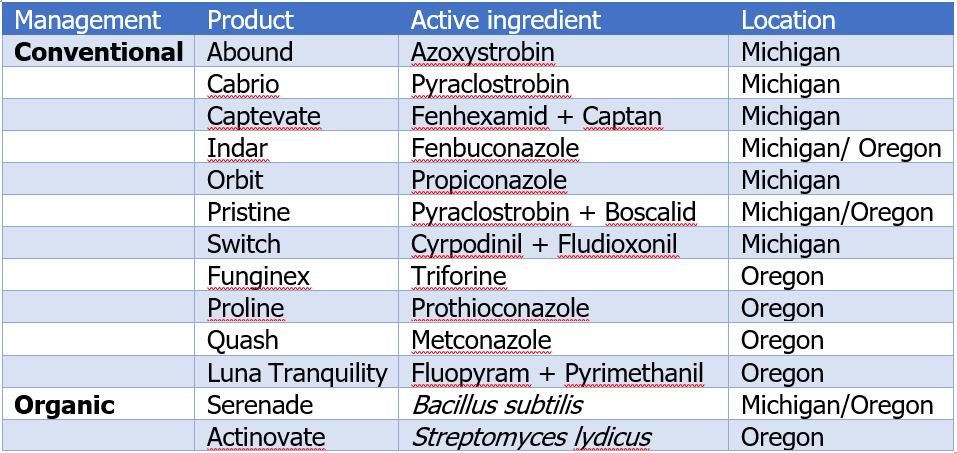

Fungicide applications during budbreak and bloom are a highly effective management strategy for mummy berry disease of blueberry, particularly when applications are timed to ascospore release and periods of host susceptibility. However, control of the primary phase of the disease has not been possible in many blueberry fields in western WA during 2017 due to record rainfall during the ascospore release period. This means that many WA blueberry growers will need to abandon sprays aimed at the primary phase and concentrate their disease control efforts at the secondary phase (ie. protecting flowers and fruit). Growers will need to carefully scout fields to determine the timing and severity of primary strikes and use that information to time sprays aimed at the secondary phase. Mummy berry fungicide efficacy studies have generally evaluated the effectiveness of disease control products aimed at both the primary and secondary phases of the disease. Table 1 gives an overview of products that have been shown to have efficacy in reducing fruit infections in Michigan and Oregon (Pscheidt 2014; Schilder et al. 2008).

Research in Georgia showed that newly opened flowers are the most susceptible to mummy berry infections (Ngugi et al. 2002) and that highest efficacy of fenbuconazole and azoxystrobin was obtained when fungicides were applied at full anthesis rather than pre-anthesis stages (Tarnowski et al. 2008). In addition, Georgia researchers found that disease incidence was reduced if pollination occurred at least one day before conidia entered the flowers. Therefore, fungicides should be applied to protect flowers and fruit from the secondary inoculum (conidia) produced on primary strikes. In addition, strategies that promote early pollination may also contribute to effective management of the secondary phase of mummy berry (Ngugi et al. 2002).

WSU Small Fruit Pathology – Current research

Current research activities of the WSU Small Fruit Pathology group related to this blueberry disease involve validation of an ascospore prediction model and studies of fungicide resistance of the mummy berry pathogen. Fungicide resistance studies are performed using agar plate assays where active ingredients of commonly used fungicides are added to the growth media to determine the effect of the chemical on fungal growth compared to the controls where no chemicals are added. These experiments aim to obtain a better understanding of the efficacy of the individual chemicals in reducing growth of the mummy berry pathogen.

References

Batra, L. R., and Batra, S. W. T. 1985. Floral mimicry induced by mummy-berry fungus exploits host’s pollinators as vectors. Science 228:1011-1013.

Cox, K., and Scherm, H. 2001. Gradients of primary and secondary infection by Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi from point sources of ascospores and conidia. Plant Disease 85:955-959.

McArt, S. H., Miles, T. D., Rodriguez-Saona, C., Schilder, A., Adler, L. S., and Grieshop, M. J. 2016. Floral scent mimicry and vector-pathogen associations in a pseudoflower-inducing plant pathogen system. PLoS ONE 11:e0165761.

Ngugi, H. K., Scherm, H., and Lehman, J. S. 2002. Relationships between blueberry flower age, pollination, and Conidial Infection by Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi. Phytopathology 92:1104.

Pscheidt, J. W. 2014. Summary of materials for management of mummy berry of blueberry from 1995 to 2013. in: Fruit and ornamental disease management program 2014

J. W. Pscheidt, ed. Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon.

Schilder, A., Wharton, P. S., and Miles, T. D. 2008. Mummy Berry. Michigan Blueberry Facts Extension Bulletin E-2846.

Tarnowski, T. L. B., Savelle, A. T., and Scherm, H. 2008. Activity of Fungicides Against Monilinia vaccinii-corymbosi in Blueberry Flowers Treated at Different Phenological Stages. Plant Disease 92:961-965.